East Bay Punk Digital Archive

Stefano Morello, English

Faculty Advisor: Eric Lott

NML Awards: The New Media Lab Digital Dissertation Award (April 2019), The Social Justice Award (June 2018)

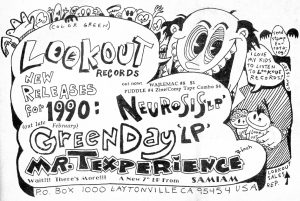

The East Bay Digital Punk Archive is an open access archive that aims to provide free and democratic access to the subjugated knowledge produced by several subcultural formations that emerged in the San Francisco Bay Area between the early 1980s and the mid 1990s. Lawrence Livermore’s Lookout! magazine (1984-1995), yet to be collected in its entirety in any institutional archive, plays a central role in this project, as it represents an extraordinary, previously unearthed, document of punk’s alternative modes of existence and production of knowledge.

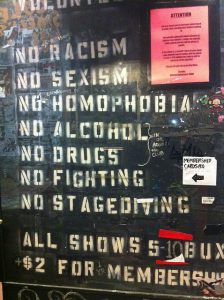

In the early 1990s, the East Bay punk scene had come to represent a quasi-utopian space in the punk imaginary worldwide, a space epitomised by the Gilman Street Project, a non-profit, all-ages, collectively organized music venue that opened its doors in Berkeley in 1986 and has, ever since, been hosting DIY shows, art exhibits, poetry readings, and other events. The very inception of Gilman gave way to a new wave of punk informed by promises of inclusivity and an aesthetic of silliness in response to the celebration of hyper-masculinity of the so-called hardcore movement that preceded it.

If the subcultural formations that emerged from Gilman provide insights into punk’s critique of the modes of exclusion of normativity (and heteronormativity) this archive will allow access to an otherwise elusive modes of cultural production that, especially with the advent of mainstream punk, has been relegated to the background. I am particularly interested in the generative function of the literature (mostly zines and letters) that, in preceding the music, suggests a longing for a future and unapologetic demands for a “time and a place where their desires are not toxic,” as José Muñoz would have it.[1] Zines — manifestos of ordinariness, scripts for the scene to come — flyers, and posters will provide, through their poetics of amateurism, a behind-the-scenes outlook of the underground punk networks and dialectics that developed within and without the United States.

In developing my project, I am siding with Golnar Nikpour’s argument against the assimilative thrust of “punk studies” as the latest object of cultural capital. “Punk,” Nikpour reminds us, is “auto-archiving, self-aware, and interested in its own history [and] operates on the premise that everyone is an expert.”[2] Hence the necessity for collaborative punk scholarship and, as suggested by Jayna Brown, Muñoz, and Tavia Nyong’o, with reference to Fred Moten and Stefano Harney’s The Undercommons, a vision of “study” as a speculative practice that can be with and for people where they are.[3] As punk becomes increasingly institutionalized (as exemplified by NYU and Cornell University’s recent acquisitions), it is crucial to maintain not only free access to its cultural production, but also to review it in conversation with its very creators. In my endeavor to create a digital punk archive I thus fully embrace Lost & Found’s methodology: as I am, and will be, unearthing and digitizing zines, posters, mixtapes and other material from personal archives, I position my work at the intersection of scholarly investigation and cultural preservation, emphasizing the importance of collaborative and archival research.

[1] Josè Muñoz, Cruising Utopia: The Then and There of Queer Futurity, (New York: New York University Press, 2009), 102.

[2] Golnar Nikpour, “White Riot: Another Failure…” Maximumrocknroll, Jan 17, 2012. Accessed online, January 20, 2018 http://www.maximumrocknroll.com/white-riot-another-failure/

[3] Jayna Brown, Tavia Nyong’o, and Josè Muñoz, “Introduction,” in “Punk and Its Afterlives,” special issue Social Text 116, no. 3 (2013).